6 Standout Works at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale

Installation view, from left to right and front to back, of Samia Zaru, Life is a Woven Carpet, 1995, and Life is a Woven Carpet, 2001; and works by Abdulrahman Al-Soliman and Hind Nasser in “After Rain” at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, 2024. Photo by Marco Cappellletti. Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

Often, art events in Saudi Arabia show a predilection for the bright and shiny. The second edition of Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, the nation’s major biennale, however, was no such show. Launched with expansive international ambitions, the exhibition showed a geographically diverse range of artists from the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Organized by the Diriyah Biennale Foundation and led by artistic director Ute Meta Bauer, the second edition of the biennial opened on February 20th and runs through May 24th in JAX District, a creative area in the historic town of Diriyah, home to the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Al-Turaif, near the Saudi capital of Riyadh.

Featuring 177 works by 100 artists and artist groups from Saudi Arabia and around the world, and including 47 new commissions, the exhibition is named “After Rain.” It’s a significant moment for the contemporary art biennial, in a country that is undergoing rapid social change, in the midst of a region experiencing intense turmoil and a disruption to the global geopolitical order.

Portrait of Ute Meta Bauer by Christine Fenzl. Courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation.

“We absorbed so much information on how artists look at and reflect on their cultural histories: the places where they work, the climate, the geopolitical histories, the materials, and the knowledge that is transmitted through artistic practices,” Bauer said in an interview with Artsy. “‘After Rain’ responds to that, the feeling of being in a biennale as a living entity, rather than a static display of works,” she added.

Even amid the overwhelming onslaught of art present in any international biennale, several artworks at Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024 stood out, especially those from or inspired by regions not normally covered in the art world circuit. Here we select six standout works.

Citra Sasmita, “Timur Merah Project,” 2019–present

Balinese multidisciplinary artist Citra Sasmita’s work is widely known for unravelling myths and misconceptions about her nation’s art and culture, and particularly for its focus on spotlighting female-centered narratives that reflexively counter colonial legacies. Recently featured in several major international platforms such as the São Paulo Bienal 2023 and the Biennale of Sydney 2024, Sasmita’s paintings, sculptures, and installations draw on traditional Kamasan painting with its trademark figurative and narrative compositions.

For the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, Sasmita exhibited new work from her “Timur Merah Project” (2019–present). The expansive installation, comprising fabric and carved wooden pillars positioned horizontally to a highly dramatic effect, traces the spread of Islamic culture across the Indonesian archipelago, its arrival through sea routes, and the historic relevance of the iconic port of Nusantara. The artwork is particularly impactful given its context, placing the storied history of Bali’s influential Islamic and Hindu civilization in a major biennale in Saudi Arabia.

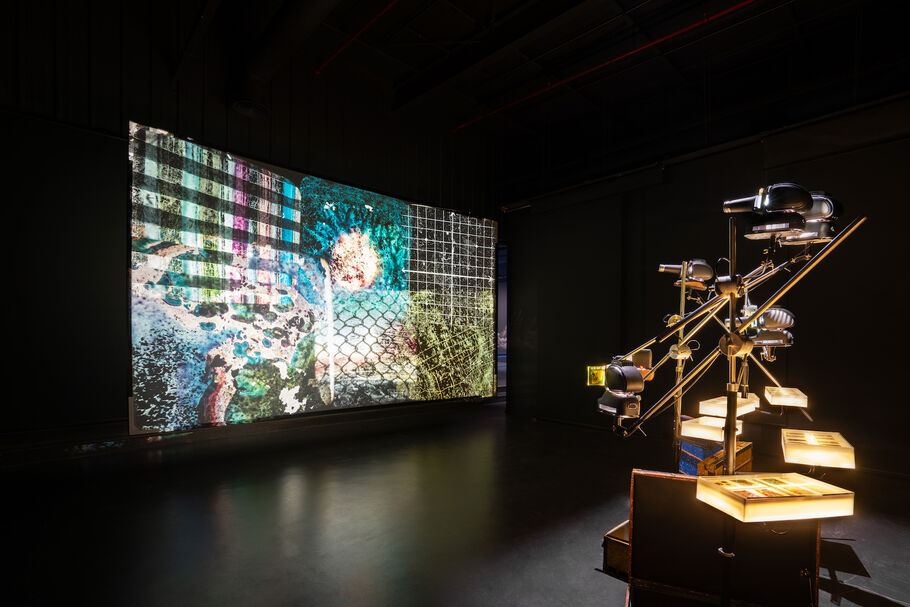

Phi Phi Oanh, A Light Exists in the Spring, 2013–present

Phi Phi Oanh, a very familiar name in the Southeast Asian art scene, has been working with Vietnamese lacquer painting (tranh sơn mài) for two decades. With a background in painting, she explores this historical technique to engage its material elements and expand its form. Having exhibited across major institutions and biennales in Asia Pacific, Oanh’s work at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, A Light Exists in the Spring (2013–present), adapts old slide projectors and rescaled clear film in display cases to render colorful images of microscopic worlds as a projection.

The installation, which turns lacquer paintings from physical objects into intangible light projections, brings to mind telescopic views of the universe. In this work, biennale visitors find themselves confronted with sci-fi, cosmic imagery through a centuries-old medium.

Dhali Al Mamoon, Kather Nripati (Wooden Lord), 2021

Dhali Al Mamoon is an artist and educator engaging with the history of Bengal and the persistence of colonialism as a historical trauma, excavating memory and meaning through nuanced visual and corporeal installations. His works are in the collections of the National Art Gallery in Bangladesh, the Ibsen Museum in Norway, and the Fukuoka Asian Art Museum in Japan, among others.

With his 2021 installation at the biennale, Kather Nripati (Wooden Lord), Mamoon’s interest in everyday objects comes across quite blatantly. The assembled kinetic sculptures border on the macabre, thanks to their arms and legs clattering in all directions, rotating periodically on various plinths, near the entrance of the very first gallery, immediately setting the tone of the biennale.

The sculptures are inspired by palm-leaf puppets that poked fun at the flailing movements of Indian soldiers who were hired by the British East India Company, known as sepoys. These dolls were a form of resistance to colonial imperialism, and as elsewhere in Mamoon’s body of work, these jittering objects question the typical order of power in society.

Hamra Abbas, Mountain 5, 2023

Hamra Abbas is clearly having a moment right now. The artist, represented by one of the region’s biggest galleries, Lawrie Shabibi, currently has a major public art installation on Dubai’s Alserkal Avenue. Titled Every Color is a Shade of Black (2024), the work is part of the artist’s ongoing exploration of color in the context of faith, identity, race, beauty, and more.

At the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale 2024, this moment continues with Mountain 5 (2023), the largest work in her series of mosaic panels depicting the world’s second-highest peak, K2. Though this mesmerizing artwork is filled with soothing hues, it was created through a tumultuous process, by cutting and joining lapis lazuli stone, which is then fixed to a granite base, before finally polishing the work to reveal the landscape that is presented in an all-black, walled gallery space at the biennale.

Abbas’s dextrous use of medium began from a very personal place for the artist. In 2015, upon returning to Pakistan, her homeland, the artist began to incorporate marble inlay from the local factories, adding a new permanent and tangible dimension to her work.

Zarina Bhimji, Yellow Patch, 2011

Turner Prize nominee Zarina Bhimji works with film, sound, photography, sculpture, and textiles, primarily focusing on distilling the triangular historical relationship between East Africa, India, and the United Kingdom.

Trained at Goldsmiths and the Slade School, Bhimji makes work informed by archival research and extensive fieldwork, and her filmmaking is filled with painterly compositions, crafted camera movements, saturated colors, textures, and layered soundtracks.

Bhimji’s work at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, Yellow Patch (2011), is no different. Shot in India as the second part of a trilogy also comprising Out of Blue (2002) and Jangbar (2015), the immersive, single-screen installation relies on light, shadow, and textures in its slow-panning shots across the Victorian-era offices of the Mumbai Port Trust, the desert landscape of the Ran of Kutch, the Indian Ocean near the port of Mandi, and various structures in western Gujarat.

Shot on 35mm film, these four main locations across the Indian subcontinent reference the migration of Bhimji’s father in colonial times. However, it is the soundtrack of the video work that steals the show, layering atmospheric field recordings with audio speech excerpts by political figures connected to the region (Mahatma Gandhi, Lord Mountbatten, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and Jawaharlal Nehru), along with music performances by Tanzanian singer Bi Kidude and Pakistani musician Abida Parveen, to create a whirlpool of song and motion that aligns with the imagery.

Taus Makhacheva, Charivari, 2019

One of the most prominently displayed and physically expansive installations at the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale is Charivari (2019) by Taus Makhacheva. Known for exploring complex histories and myths through humor and imagination, the artist often taps into her personal history of growing up in the Republic of Dagestan, a mountainous Russian region in the North Caucasus, in her body of work.

The installation at the biennale cleverly breaks with tradition to invite visitors to step on the raised white platform where various mannequin-like figures stand in differing garb and poses. The work is inspired by the term “Charivari,” which refers to the fast, spectacular gymnastic feats performed by acrobats and clowns.

Accompanied by audio narratives and commentaries based on archival research and oral interviews in Baku, the installation offers a fascinating glimpse into the Soviet history of the Baku State Circus in the Republic of Azerbaijan. Ultimately, the artwork compels biennale visitors to question social norms, drawing on the experimental and absurd aspects of avant-garde art.